GAME 6

GAME 6 – April 4, 2024

Fourteen scoreless innings and cold temps

meant even fewer fans in the

stands for the second game of

the doubleheader, but

those that remained were

rewarded with

a feel-good

walkoff

win.

Fourteen scoreless innings and cold temps

meant even fewer fans in the

stands for the second game of

the doubleheader, but

those that remained were

rewarded with

a feel-good

walkoff

win.

Canada Goose shields from cold and wind.

Bud and others are remembered.

Rhys returns and trouble brews.

Benches, bullpens empty.

A long ball that clanked

off of the wall,

but it was

only

one.

mets #2024metshomegames #fullseasonticketholder #thecitilife #budharrelson #rhyshoskins

This blog has been a place for me to share my observations about similarities between two subjects about which I am passionate: classical music and baseball. Because the sport I love and write about is a team sport, my analogies have tended to center around what it means to perform as an individual on a team—a baseball team or an orchestra—at the professional level.

I was fascinated, then, to read the personal observations about similarities between classical music and sports by none other than our Music Director at the Metropolitan Opera, Yannick Nézet-Séguin!

I found what he had to say particularly interesting because his basis of comparison was not to a team sport but to a solo sport: professional tennis.

I particularly liked how he suggested that an appreciation of sports in general and tennis in particular could be seen as a “gateway” to enjoying classical music:

Classical music and opera in general is [like professional tennis] also something that you can just sit and watch people really sweat and give their all at the service of something that’s very beautiful. It’s a very human experience when you see people giving their all on their instruments and sweating it.

It’s maybe what can draw sports fans who probably sometimes think, Oh, I love sports. I don’t really like art. But maybe they forget that great art, the way we do it, is also witnessing a human reaching the peak of or outdoing themselves and just going beyond their human limits.

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

I read Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s observations in a thought-provoking interview he recently gave to Sports illustrated. You can read the interview in its entirety here.

The interview was written in anticipation of an appearance by our Music Director, some of my MET Orchestra colleagues, and baritone Will Liverman at Arthur Ashe Stadium. The musicians provided a musical prelude to the Men’s Finals of the U.S. Open last Sunday, September 10th.

Here’s a video of the performance:

Yogi Berra’s famous adage is applicable to many pursuits in life. I would like to think that for me, learning ain’t over until my departure from this earth.

My husband, Garry Spector, has a PhD in chemistry from Columbia University. He possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of all things baseball, particularly the sixty-year history of our beloved Mets franchise. He also knows far more about classical music, including opera, than many of us in the industry itself. His knowledge and remembrance of historical events of significance and their respective dates is positively intimidating.

But what my husband doesn’t possess is vanity. He knows so much about all of these subjects because his fascination with them has fueled a lifetime of voracious reading and regular attendance at baseball games, concerts, and operas.

Garry frequently shares anecdotes, facts, and trivia when either the day’s date or a current event triggers his memory of a related event in history. This he does, not to flaunt his vast knowledge, but because of his genuine enthusiasm for the subject at hand.

I would never think nor try to compete with Garry’s comprehensive knowledge, but in our twenty-seven years of marriage, he has seemed delighted to hear my own stories and anecdotes about classical music from my thirty-five years working as a professional musician. He particularly delights in hearing many of the stories I have from my thirty years as a member of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra.

If Garry has any “blind spots,” he readily admits that there are gaps in his knowledge, particularly of popular culture. It was particularly delightful to be able to fill in one of those “gaps” for him involving baseball—a subject about which I am a novice compared to him.

A life-long follower of the Mets, Garry grew up listening to the radio voice of the late Bob Murphy. Early on in our shared baseball life, I learned that it was Murphy’s voice decrying the famous “It gets by Buckner!” call that is near and dear to Mets fans of all ages. He has casually mentioned some of Murphy’s delightful terminology.

When the subject of a doubleheader came up some years ago, Garry admitted that that was one of Murphy’s expressions that he had never understood.

In single admission doubleheaders, the second game follows shortly after the first game has concluded. On other occasions, like today at Citi Field for example, two separate games with separate admissions are scheduled. This is called a day-night doubleheader—what Bob Murphy referred to as a “Cole Porter affair.”

How thrilling it was for me to be able to fill this infinitesimal gap in his broad and thorough knowledge of all things baseball!

I explained that one of Cole Porter’s most famous tunes was “Night and Day.”

There have been only a few times like this where my knowledge of popular culture has served to add meaning or perspective on either baseball or opera. On road trips to see the Mets, we have been at several ballparks where an organist has played the players’ walkup music. There have been times where I smile, knowing the words to the melody the organist plays for specific players and how they serve as a musical commentary to either their name or appearance. These “inside jokes” are mostly lost on Garry.

It doesn’t happen often, but on those occasions when I can “teach” Garry something that he doesn’t know related to baseball, we both enjoy it. As far as we both are concerned, we “ain’t over” learning new things until “it’s over.”

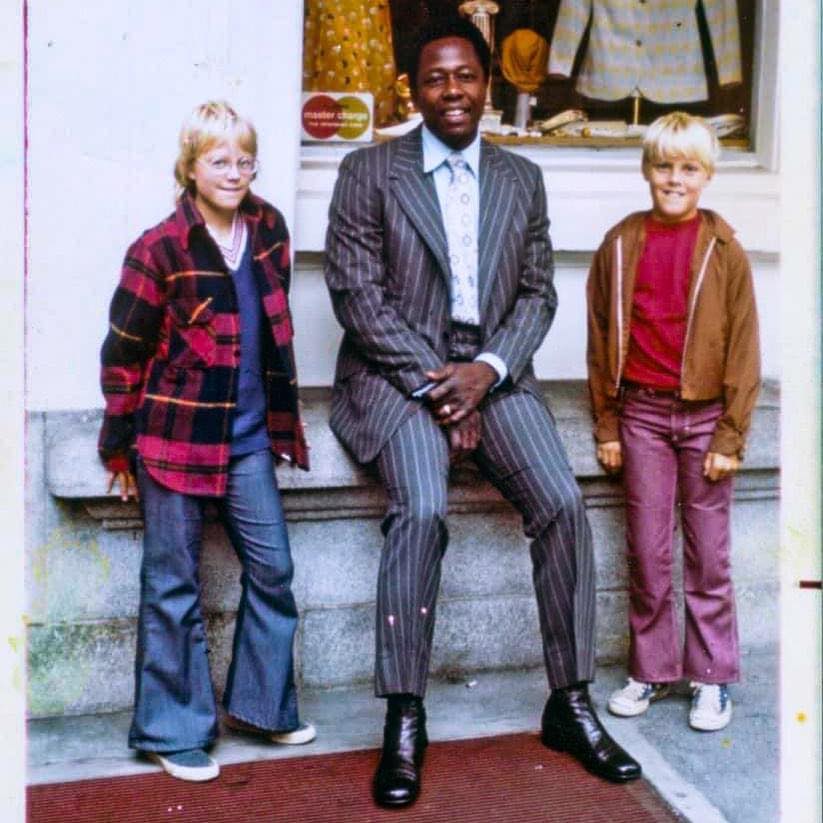

Anyone who thinks that Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier and acceptance for other ballplayers of color followed closely behind is, of course, sadly mistaken. Baseball is full of disgusting tales of prejudice and inequalities persistent well beyond Robinson’s career.

As much as I have enjoyed reading all of the tributes written in homage to the late Hank Aaron, I feel it’s imperative that his accomplishments be remembered within the context they were achieved.

Hank Aaron was no stranger to white rage throughout his career, but the volume was turned up tremendously as he grew closer to breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record. In various autobiographies and biographies and in published interviews he was unambiguous about the pain and suffering he and his family had suffered because of prevalent racist attitudes:

“April 8, 1974, really led up to turning me off on baseball. It really made me see for the first time a clear picture of what this country is about. My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ball parks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won’t go away. “

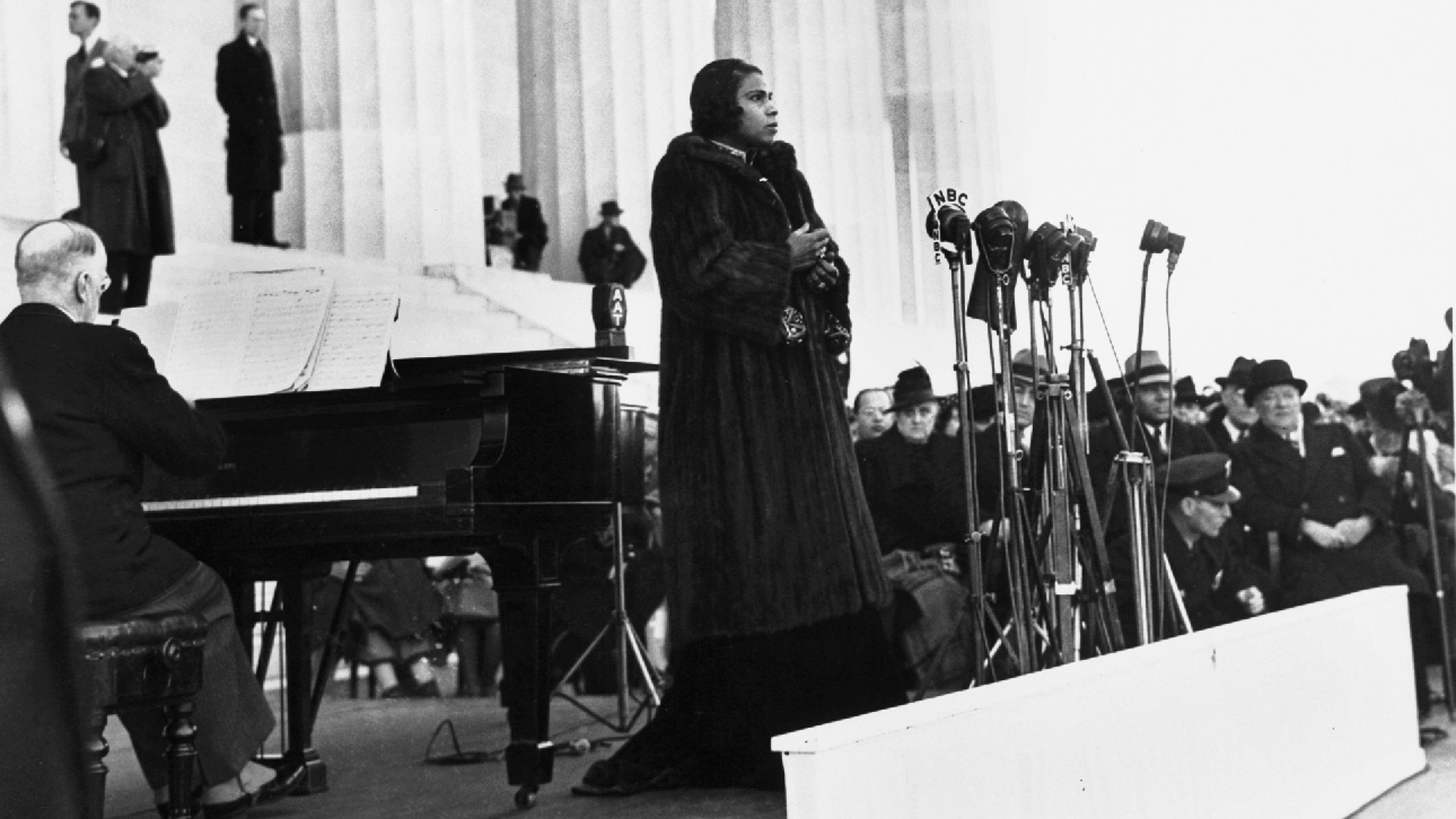

The contralto Marion Anderson was arguably the “Jackie Robinson” of the opera world. In 1955, she became the first Black singer to sing a solo role at the Metropolitan Opera. But perhaps more well-known than that debut was her appearance singing at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., in 1939 for a crowd of 75,000. She had been denied the venue of Constitutional Hall in Washington by the DAR who cited a “white-artist-only” clause in their contractual agreements for appearances in the building which they owned.

Like athletes of color, black singers have continued to experience both overt and subtle racism long after Anderson’s MET debut. For some, that has kept them from the opera stage. For others who did have careers, one has to wonder what they endured to get there and what they suffered to remain in the spotlight. Also, was the color of their skin perhaps a reason why some of them are not more widely known? And what voices of perhaps similar beauty and musical excellence were never recognized nor heard?

The previous year saw public outcry over the murder of George Floyd, nation-wide peaceful protests in support of Black Lives Matter, and organizations–including Major League Baseball and the Metropolitan Opera–taking a good hard look at ways that they have been a part of the problem in persistent racism in this country. We have also seen the election of the first Black Senator from Georgia–all very positive events.

But the past year also saw a tone-deaf administration abandon its job of dealing with a pandemic that has been found to disproportionally affect Americans of color. We have seen blatant voter suppression and attempted disenfranchisement of lawful voters from urban, i.e., predominately Black districts. We had no sooner turned the calendar than the entire world witnessed an attempted coup against the Legislative branch of our government perpetrated by domestic terrorists, a number of whom openly espoused racist and antisemitic rhetoric and slogans and who were aided and abetted by others with the same white supremacy proclivities and agenda.

Until this country has a reckoning with its racist past in some sort of meaningful way, I fear that it will ever be this way: three steps forward, two steps back. And I don’t have a lot of confidence in any such national awakening happening, I’ll be honest. But there is one thing about which I am certain: there will be Black Americans who rise to the top of their disciplines and fields despite the senseless and disgusting impediment of racism that is put in their paths.

But, I too have a dream: that one day we the public will be able to see all of the rich Black talent–in sports, in classical music, and in all other arts and sciences and human endeavors. There are certainly those figures who have excelled in spite of their detractors. But imagine those whose talents that we never were allowed to enjoy and experience simply because the hate and cruelty were too great for those individuals to persevere in their pursuit of greatness?

It’s not an understatement to say that I went into a depressive funk following the event of January 6 2021. But, while marking Martin Luther King, Jr.’s work and legacy about a week later, I tried to keep in mind his perseverance and the phrase he often included in his sermons:

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.“

If you watched the Inaugural ceremony, perhaps you were inspired by the animated reading and thought-provoking words of Amanda Gorman, National Youth Poet Laureate. I certainly was.

I’ve tried to retain the spirit of optimism that is so deeply embedded in her poem “The Hill We Climb,” an excert from which I include below:

And so we lift our gazes not to what stands between us,

but what stands before us.

We close the divide because we know, to put our future first,

we must first put our differences aside.

We lay down our arms

so we can reach out our arms

to one another.

We seek harm to none and harmony for all.

Let the globe, if nothing else, say this is true,

that even as we grieved, we grew,

that even as we hurt, we hoped,

that even as we tired, we tried,

that we’ll forever be tied together, victorious.

Not because we will never again know defeat,

but because we will never again sow division.

Ms. Gorman penned these words in response to the events of January 6th. Perhaps I would do well to look to her and Millenials like her–those who remain positive in the face of their generation’s less than bright immediate future and who tend toward idealism–for inspiration.

Yes, you’ve come to the right place. If you arrived here expecting to read something about the Metropolitan Opera, you have not clicked on this link in error.

As with so many things in the music world, current events at the Metropolitan Opera remind me of similar events in the world of baseball. And that’s this blog’s raison d’être.

I somehow could not find the inspiration for blogging about my team in 2020–a season dramatically reduced in the number of games and one in which I was not welcome in my usual seat in Section 318.

I was positively itching to write, however, when I recently read a Twitter thread by a former Metropolitan Opera colleague.

In spite of being closed since the middle of March, the Metropolitan Opera found itself making headlines over the long weekend.

Basically, I have a problem with the name of this entire series: “Met Stars Live in Concert.”

Setting aside the crux of the news for a moment—the unfair labor practice involved in my employer hiring non-union musicians (for the third time)– I would like to focus specifically on semantics.

Basically, I have a problem with the name of this entire series: “Met Stars Live in Concert.”

Make no mistake: members of the MET Orchestra, MET Chorus, MET Music Staff, and MET Stage Crew truly value the solo artists who participated in the New Year’s Eve gala, and those who have participated in other virtual fundraising performances and regular performances at the MET. I think it’s safe to say that we ALL are inspired by their artistry and our thrilling collaborations with them. We also readily acknowledge and respect that many ticket buyers recognize their names but probably wouldn’t know the names of many, if any, individuals in the groups mentioned above.

But, as many of these artists are the first to admit, without these “unsung heroes”–the groups of employees supporting them and assisting them, opera simply would not happen, and those artists certainly would not be in a position to do their best work.

Thinking about the symbiotic relationship between solo artists and full-time employees at the MET made me think about a similar relationship in baseball. I wondered: How do those players who’ve played every single game for their team for the first two-thirds of the season feel when they find themselves in the dugout sitting next to some newly acquired star who’s brought in on a temporary basis?

Major League Baseball rules require that in order for a player to be eligible for postseason play, he must have been playing on the team in contention prior to September 1st. When it gets to mid-August, teams who have little or no chance of postseason play often field offers from other (winning) teams, and many times those teams end up dealing players to teams who are likely to make the postseason. Because these players have not played the bulk of the season with the team to whom they are traded, and because they often are not offered or do not accept a contract with that team once the postseason is over, these late-season acquisitions are known as “rentals.”

Baseball history is rife with just such “hired guns” who have, late in the season, gone from a losing team to a winning team in the latter’s hope of the player providing that extra spark needed to get them a World Series berth.

A player familiar to New York baseball fans, pitcher David Cone, found himself in the starring role of “gunslinger for hire” on several occasions during his career. He was traded by the Mets in late August of 1992 to the Toronto Blue Jays, earning World Series rings for himself and the team. He signed with the Royals in the off-season, then returned to Toronto in 1995, and was once again a late-season trade, dealt to the Yankees this time. You can read here about even more players who have played this somewhat unique role at times in their careers.

While it’s very exciting–for the team as well as the fans–when these big boppers or pitching phenoms are brought in to “save the day,” winning is still dependent upon the play of the entire team. The players that have been wearing the uniform from the beginning of the season, grinding it out, game after game–these are the players that got the team its winning record. Not only that, but chances are good that that star player will not be on the team when Spring Training begins in February, regardless of his postseason performance.

Similarly, there’s no question that solo artists are the ones that most often produce the high C’s, the inimitable concluding pianissimo high note that tapers to nothing, the character representation that is so authentic that one forgets that this is theater. Those of us working in the house every day and every night do not begrudge the resulting plaudits, the cheers at the end of arias, nor the curtain calls at the end. They are justly deserved and, many times, many of us in the pit and in the wings are also openly cheering and applauding along with the audience.

However, calling any of these solo artists “MET Stars” seems somewhat misleading and disingenuous to me.

“… how is any solo artist a ‘MET Star’ any more than he or she is a ‘Covent Garden star,’ a ‘Wiener Staatsoper Star,’ a Bayerische Staatsoper star,’ or a ‘La Scala star?’”

For one thing, the MET cannot make sole claim to these artists nor how they are received; these artists experience the same merited accolades everywhere they perform. By design, their profession dictates that they travel to and sing in MANY opera houses and halls. And, incidentally, solo artists negotiate and sign their own individual contracts with each venue, i.e., they are not employees of any one opera house but are classified and paid as independent contractors.

Considering that, how is any solo artist a “MET Star” any more than he or she is a “Covent Garden star,” a “Wiener Staatsoper Star,” a Bayerische Staatsoper star,” or a “La Scala star?”

Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Opera’s full-time employees are there day after day, night after night, and season after season, performing our OWN feats of technical and aesthetic brilliance.

Many of us, myself included, were here well before some of these artists made their MET debuts. And many of us will be here long after they retire. Some of us played and worked at the OLD MET (which closed its doors fifty-five years ago!)

So, secondly, doesn’t that make full-time tenured employees stars in our own right?

Stars come and go. Meanwhile, the rest of us have been busy playing, singing, dancing, rehearsing, accompanying, coaching, prompting, pounding nails, moving sets, wiring, powering, lighting, storing and handing out essential props, calling personnel to the stage for the smooth execution of the opera without unnecessary traffic jams in the wings or missing characters or props, sending people onstage at JUST the right moment, perfectly timed to the music and action—and delaying such when occasionally needed for various reasons, arranging and moving chairs and stands and delicate equipment like harps, pianos, and percussion equipment, securing sheet music for every opera, making sure all cuts or changes are made for EVERY person—solo artists, chorus members, orchestra personnel, conductors, and retrieving parts to make additional changes when they inevitably happen prior to and during the rehearsal period for any number of reasons—a conductor wants to make or open a cut, a singer requests that an aria be transposed, stage action necessitates more or less music, etc. We are also taking measurements, cutting fabric, sewing costumes, repairing existing costumes, touching up scenery, making wigs, putting makeup on cast members, fitting cast members into costumes, laundering costumes, ironing costumes, meeting with directors about their ideas for sets and costumes, loading sets on trucks to be taken to storage units in New Jersey…whew! I’m out of breath!

“…we are a well-oiled machine that has been decades in the making.”

If this all sounds complicated, trust me: it IS. If it sounds like there are a lot of different groups of folks charged with a lot of responsibility, there ARE. But because every one of these employees is the crème de la crème in their respective fields, most of the time, the effort involved in any one performance is hidden from view. It’s “all in a day’s work” for us: our art or craft has been refined and honed through years and years of doing what we do and passing along the best of those traditions to those who come in to the MET family either directly from school or from other theaters.

In short, we are a well-oiled machine that has been decades in the making.

To paraphrase the great conductor Arturo Toscanini, perhaps the only true stars are in heaven.

So, then. Are WE the MET Stars?

To paraphrase the great conductor Arturo Toscanini, perhaps the only true stars are in heaven.

It’s the All-Star Break and this Mets blogger is about as inspired and productive as her team. Sigh…

I am, however, proud to announce that Garry Spector, inspired from the previous week’s 1969 Anniversary celebrations, will be a guest blogger on this site in the very near future!

If you are interested in the past and history beyond the realm of baseball, I invite you to view a second blog I created today which is to be informed by and devoted to another of my passions–genealogy.

Check it out and, if you like what you see, please subscribe!

In the meantime, watch this space for an upcoming post on Tom Terrific from my terrific husband!

In 2005, my family and I purchased a Mets partial season ticket plan. A lot of wonderful things were to follow.

Some of them even involved the games themselves.

The following year, anticipating the ticket demand resulting from the team’s upcoming move from Shea Stadium to Citi Field, we ponied up and became full season ticket holders. We have continued to renew our plan every year since then.

At first, my husband and I didn’t always see as much of the games as we might have liked, our young daughter’s attention span often limiting us to four or five innings at most. Her interest–and longevity–increased with age. She learned more about the game and its history. She read and learned about our players and their positions, and she developed a particular affinity for certain players. Her involvement with and appreciation for baseball reached an even higher level when her father taught her how to score and she began keeping a score book.

With each passing year and season, our shared experiences have brought our family closer together. We have made new friendships—with those regulars seated near us, with members of the media (particularly the Mets Radio personnel), with members of the Citi Field Season Ticket Account Services staff, as well as with members of the Security detail and Concessions staff. Some members of our “summer family” have become year-round friends. We have made road trips to see the Mets, our travels taking us to see them play in every single National League ballpark and even a few American League parks. Those road trips have been coupled with side trips to historical and cultural attractions in those cities and have provided opportunities to see family and friends in the area.

From a personal standpoint, my interest in the Mets rekindled my passion for writing, resulting in the creation of this very blog. Going to an average of eighty games a year, I found myself looking for images that were unique to each game or home stand and wanting very much to document what I saw. I was inspired to take photography classes, and I acquired more sophisticated equipment. The results were images that were a step above those I had previously shot: in composition, control, and resolution.

With years of photos on my hard drive, it took me a while to assemble some of my favorite photos of David Wright for this slide show. These photos (and videos) were shot during games and batting practice at Shea Stadium, Citi Field, and in Port St. Lucie; at RFK Stadium and Nationals Park; at Dolphin Stadium and Marlins Park; and at Citizens Bank Park, Turner Field, Wrigley Field, Great American Ballpark, Miller Park, PNC Park, A T & T Park, PetCo Park, Dodger Stadium, and Minute Maid Park, as well as at special Full Season Ticket Holder events.

Because my family and I have been Mets season ticket holders since just about the time David Wright came up to the big leagues, in some ways it feels like we watched him “grow up” in Queens. Being at Citi Field for his final game and farewell to Mets fans this past September—after watching him play his entire Major League career with our team–it was impossible not to shed a tear.

You will be missed, dear Captain. 😢

Commentary on baseball, the Mets in particular, from the perspective of a professional orchestral musician is what one usually finds on this site. This particular post, though, will focus on a colleague and close friend of mine and the ways in which he was a great “teammate.”

Commentary on baseball, the Mets in particular, from the perspective of a professional orchestral musician is what one usually finds on this site. This particular post, though, will focus on a colleague and close friend of mine and the ways in which he was a great “teammate.”

My orchestra has lost a great musician and colleague. Rich Dallessio was a freelance oboist who played for numerous orchestras here in New York, most notably the New York City Ballet. He was also a frequent substitute player with us at the Metropolitan Opera. Rich battled liver cancer for almost an entire year; he passed away last week.

Substitute players at the MET and other professional music ensembles, including Broadway shows, are like bench players: they are called on in a pinch and often don’t have a lot of time to prepare for the gig. Veteran ballplayers often shine when given those opportunities, as did Rich.

If a regular MET musician called in sick to a rehearsal or performance at the last minute, Rich could be relied upon to answer his cellphone quickly and rearrange his schedule in order to be of assistance. Once he got to the MET, he would play whatever part was needed, without any fuss, making for a seamless performance that put everyone around him at ease, not the least of whom was the Orchestra Manager who is responsible for “fielding” a full orchestra every night!

Rich was an exceptionally fine player and an inspiring musician. He also had many years of experience playing our somewhat unique repertoire, thereby making him an especially valuable commodity to the wind section of the MET.

In addition, he was, hands-down, the finest sight-reader I have ever met. I remember one performance in particular that had all of us in the orchestra, the conductor included, in awe.

Some years ago, our regular English horn player called in sick to a performance of Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schattten. Rich was asked to come in to sight-read the part for the performance, and he bravely took up the challenge.

All of Strauss’s operas feature extremely challenging virtuosic orchestral writing, often in very unusual keys. Beyond the inherent difficulty of the part itself was the fact that it had been many years since this lesser-known and less frequently performed opera had been presented at the MET. Rich had not played any of the rehearsals of the opera that season nor had he played any previous performances in the run.

The entire night, Rich was his usual unflappable, solid, reliable self. He never lost his place, which is remarkable in and of itself, but he also played the numerous solos (which he was hearing for the first time as he was playing them!) with sensitivity and nuance. It was a stunning performance that many of us in the wind section still speak of to this day.

Even as a sub, Rich certainly had the chops for solo English horn and solo oboe playing. When he found himself in the Principal chair, there was nothing apologetic or timid about his playing whatsoever. And yet, he could just as easily assume the role of Second Oboe and deftly defer to the Principal player, matching pitch, note lengths, volume, and style without ever a word being exchanged between the two players.

I know this because he played Second Oboe to me. And I played Second Oboe to him as well.

And that’s because Rich knew the joy that being a part—any part—of a winning team can be. It really didn’t matter to him where he sat or what part he played. He was in it for the team. “Put me in coach! I’m ready to play today.”

He was a utility player on the order of former Mets Kelly Johnson or Justin Turner. And, as in baseball, a player who can field more than one position can be of tremendous value, especially if he/she can perform well in the clutch. Rich was that guy.

Rich loved being part of a team. And he loved playing music. And he had an infectious laugh. I loved when all of those things came together—which they often did.

I’ll never forget the times we both played onstage in the Don Giovanni bandas together. Mozart’s Don Giovanni calls for small instrumental ensembles—bandas—in each of the opera’s two acts. The score calls for two onstage oboes in both acts. The musicians appear onstage and in costume and, for that reason, they are often involved at least peripherally in the staging.

Rich was involved in playing the Don Giovanni bandas just about every time the opera was performed at the MET. The other onstage oboe assignment usually fell to a colleague of mine, but in 1997, I lucked into my first and (so far at least) only run of performances of Don Giovanni in which I did not play in the pit but had the pleasure of playing onstage in costume along with Rich.

It was always a delight to play with Rich: his sound had a spinning, vibrant quality that reminded me of a really good coloratura soprano—Judith Blegen, Kathleen Battle, Barbara Bonney. It was a sound that was very similar to what I aim for myself, actually. That’s probably one of the reasons it was always such a pleasure playing with him and why blending with each other’s sound was so effortless.

These performances, then, were a treat for me, musically. But that was only the half of it. The fun of being in costume and part of the stage action was never lost on Rich, even after many performances of this work. Once I had gotten a few performances under my belt and became more comfortable onstage, we both had even more fun.

Near the end of Act I, Giovanni is hosting a party at which many instrumentalists are playing, e.g., the banda. Giovanni dances with Zerlina and leads her into an adjoining room to try to seduce her. She screams for help and pandemonium ensues about the time our music has ended at which time we were instructed to react in surprise and exit stage right.

While we always followed our stage directions, it seemed that with every performance, Rich and I took a little more poetic license, if you will, and made more of our very little time onstage as court musicians than we had in the previous performance. Our looks of astonishment became ever more exaggerated—wide-eyed, mouths agape. We played off of each other: he looked left, I looked right, each of us feigning an intense curiosity as to what had prompted Zerlina’s cries. While the rest of the musicians had shrugged their shoulders in a bored manner and shuffled offstage, he and I pantomimed exaggerated and extended inquisitiveness about the kerfuffle resulting in our being the last banda members to exit the stage.

I don’t think this was apparent to anyone else, and the Stage Manager certainly didn’t need to come after us with a hook, but we definitely had some great times and some hearty laughs, channeling our inner thespians for those two nights every week when that opera was being performed that season.

Rich was a mirth-filled, down-to-earth, kind and generous person. As fine as his oboe-playing was, he was an even finer human being. He will be missed at the MET, at the NYC Ballet and other ensembles in which he played, and by all of his many students to whom he devoted much time and energy.

I’m the proud friend of several prolific baseball writers. In the past, I’ve referenced here the fine work of Greg Prince and Jason Fry My seat for Mets games is in Section 318–right in front of the WOR-710 Mets broadcast booth. Over the years, the fact that I always have the Mets Booth radio guys in my ear during games–and often pantomime my reactions to their always insightful and entertaining commentary–and that I regularly trade tweets with “the immortal” Chris Majkowski during games, have resulted in a friendship with the radio personnel, including sportscaster and author Howie Rose.

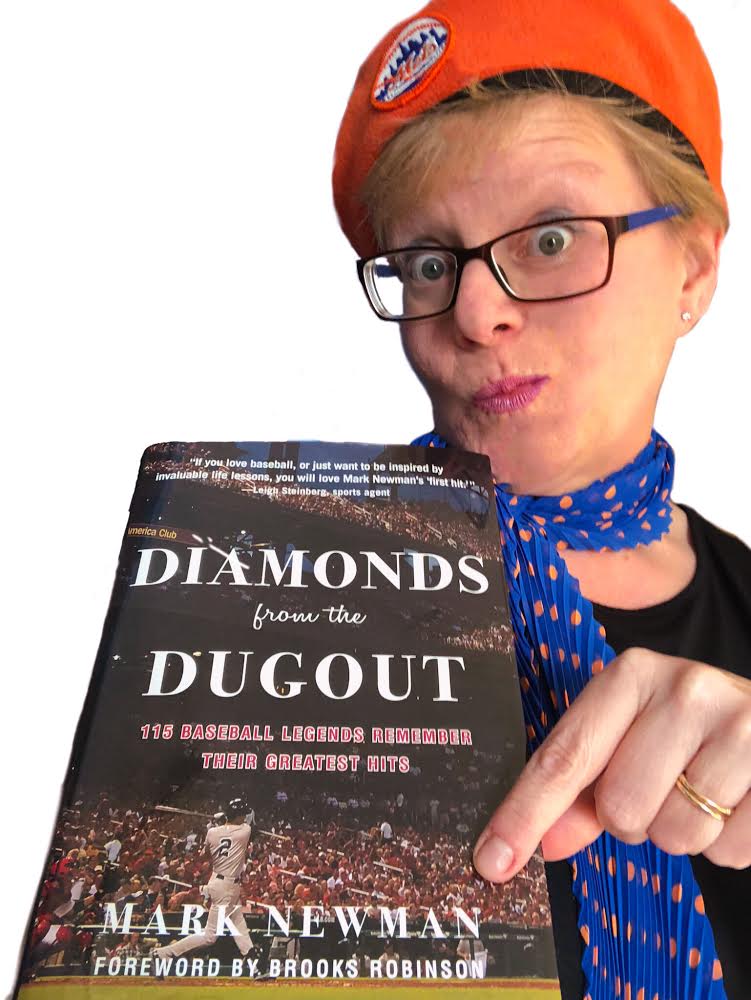

Mark Newman does not write about the Mets exclusively, but he has spent a fair amount of time at Citi Field. He has been a longtime Hall of Fame voting member of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. He is the recipient of the National Magazine Award for General Excellence. He has worked twenty-five World Series for Major League Baseball. It was through his position with MLB’s Advanced Media–for which he is currently Enterprise Editor–that I got to know him. Mark was a guru/”cheerleader”/problem-solver for all of us novice fans starting to blog about our teams for the first time. He was most helpful in providing guidance, encouragement, and helpfulf feedback to this Mets blogger. Since starting Perfect Pitch, I’ve had a chance to share some memorable games with Mark at Citi Field, and he and his wife Lisa have attended a few Opening Night Galas at the Metropolitan Opera as well.

Suffice to say, Mark has been around baseball and is accustomed to posing questions to ballplayers.

But for almost as long as I’ve known him, when he’s not involved in a specific work assignment for MLB, Mark’s been meeting one-on-one with players in pursuit of their answers to a single query: given the opportunity to cite a single at-bat as the most memorable of your career, which one would you choose?

He’s talked to current players, players who retired long ago, and Hall of Famers. He’s met them at batting practice, at foundation fundraisers, on golf courses, over lunch, dinner, or a cup of coffee–any number of scenarios that afforded the time and place for a bit of introspective reflection, “off the record” and away from the player’s team, his family, and the public.

The resulting answers, Mark found, were intriguing, fascinating, and quite often, they came as a surprise. A publisher had the same reaction. A book, entitled Diamonds from the Dugout, envisioned and written by Mark–with encouragement from Brooks Robinson–is the happy result. It came out just this week.

Fans, the media, statisticians, bloggers, and baseball historians have time-honored criteria for quantifying or qualifying an individual athlete’s performance relative to his peers. They are also afforded their respective platforms for self-cultivated “highlight reels” of their own selection. Some of the crowning points shared with Mark by these ballplayers might be seen as relatively unremarkable, from a strictly baseball point of view; what is noteworthy is the reason why this is the hit selected by the player himself and given its own chapter in Mark’s book.

The subject of each chapter is certainly a measure of athletic accomplishment, but more often a player’s selection had more to do with the context in which the hit was made. Mark skillfully weaves together the specifics of the play with anecdotal information from the player. Reading these vignettes, one can easily visualize the whimsical grin playing across the face of a player or the slight misting up of a player’s eyes involved in the hit’s memory and his retelling a story that, for that player at least, has obviously become the stuff of myth or legend. The inclusion of each player’s “back story”, the opportunity for him to “set the stage” and to add personal embellishments to his saga: this is what makes the book fascinating reading.

The book is a veritable Who’s Who of baseball royalty, but as a Mets fan, you’ll particularly enjoy reading chapters devoted to David Wright, Mike Piazza, Ron Swoboda, Mookie Wilson, Darryl Strawberry, Rusty Staub, Ed Kranepool, and Ralph Kiner. I particularly liked Staub’s tale involving a multiple-hit game as a young player for the Astros in May of 1967. The legendary Ted Williams was in the house–not as a player, but as an award presenter. Williams had scouted Staub in high school for the Red Sox, and on that day, he witnessed Staub go 3 for 3 with a run scored in the 6-2 victory. Staub recalls that his efforts that day garnered words of high praise from Williams that he remembers vividly to this day, “You’re gonna be OK, kid.”

Conversely, Mets fans will enjoy Chipper “Larry” Jones’ favorite hit for the mere fact that it did not take place against Mets pitching. Considering the plethora of killer at-bats inflicted by him upon my team, I was relieved to find that his chapter does not constitute a nostalgic recounting of a nadir of Mets family lore.

It’s a hard time for Mets fans: we had high expectations and low return this season. Meanwhile the team across town has powered its way to the ALDS. Trust me, there’s no better time to get lost in a book, if you’re a Mets fan. And I highly recommend you pick up a copy of Mark’s book today!

UPDATE: The hardcover edition of the book is once again in stock at Amazon. For shoppers in the New York City area, Barnes & Noble stores expect to have the hardcover available in its tai-state area stores and for free delivery to select area zip codes by Wednesday, October 11th.

NOTE: As of this writing, Amazon is temporarily out of stock of the hardcover edition of the book. However, it is available on Kindle for instant download. The hardcover edition is currently available on Barnes & Noble’s website , and it is also available as a download for Nook.

For more information about Mark Newman and his book, please check out his website as well.

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

(more…)

You must be logged in to post a comment.