Yes, you’ve come to the right place. If you arrived here expecting to read something about the Metropolitan Opera, you have not clicked on this link in error.

As with so many things in the music world, current events at the Metropolitan Opera remind me of similar events in the world of baseball. And that’s this blog’s raison d’être.

I somehow could not find the inspiration for blogging about my team in 2020–a season dramatically reduced in the number of games and one in which I was not welcome in my usual seat in Section 318.

I was positively itching to write, however, when I recently read a Twitter thread by a former Metropolitan Opera colleague.

In spite of being closed since the middle of March, the Metropolitan Opera found itself making headlines over the long weekend.

Basically, I have a problem with the name of this entire series: “Met Stars Live in Concert.”

Setting aside the crux of the news for a moment—the unfair labor practice involved in my employer hiring non-union musicians (for the third time)– I would like to focus specifically on semantics.

Basically, I have a problem with the name of this entire series: “Met Stars Live in Concert.”

Make no mistake: members of the MET Orchestra, MET Chorus, MET Music Staff, and MET Stage Crew truly value the solo artists who participated in the New Year’s Eve gala, and those who have participated in other virtual fundraising performances and regular performances at the MET. I think it’s safe to say that we ALL are inspired by their artistry and our thrilling collaborations with them. We also readily acknowledge and respect that many ticket buyers recognize their names but probably wouldn’t know the names of many, if any, individuals in the groups mentioned above.

But, as many of these artists are the first to admit, without these “unsung heroes”–the groups of employees supporting them and assisting them, opera simply would not happen, and those artists certainly would not be in a position to do their best work.

Thinking about the symbiotic relationship between solo artists and full-time employees at the MET made me think about a similar relationship in baseball. I wondered: How do those players who’ve played every single game for their team for the first two-thirds of the season feel when they find themselves in the dugout sitting next to some newly acquired star who’s brought in on a temporary basis?

Major League Baseball rules require that in order for a player to be eligible for postseason play, he must have been playing on the team in contention prior to September 1st. When it gets to mid-August, teams who have little or no chance of postseason play often field offers from other (winning) teams, and many times those teams end up dealing players to teams who are likely to make the postseason. Because these players have not played the bulk of the season with the team to whom they are traded, and because they often are not offered or do not accept a contract with that team once the postseason is over, these late-season acquisitions are known as “rentals.”

Baseball history is rife with just such “hired guns” who have, late in the season, gone from a losing team to a winning team in the latter’s hope of the player providing that extra spark needed to get them a World Series berth.

A player familiar to New York baseball fans, pitcher David Cone, found himself in the starring role of “gunslinger for hire” on several occasions during his career. He was traded by the Mets in late August of 1992 to the Toronto Blue Jays, earning World Series rings for himself and the team. He signed with the Royals in the off-season, then returned to Toronto in 1995, and was once again a late-season trade, dealt to the Yankees this time. You can read here about even more players who have played this somewhat unique role at times in their careers.

While it’s very exciting–for the team as well as the fans–when these big boppers or pitching phenoms are brought in to “save the day,” winning is still dependent upon the play of the entire team. The players that have been wearing the uniform from the beginning of the season, grinding it out, game after game–these are the players that got the team its winning record. Not only that, but chances are good that that star player will not be on the team when Spring Training begins in February, regardless of his postseason performance.

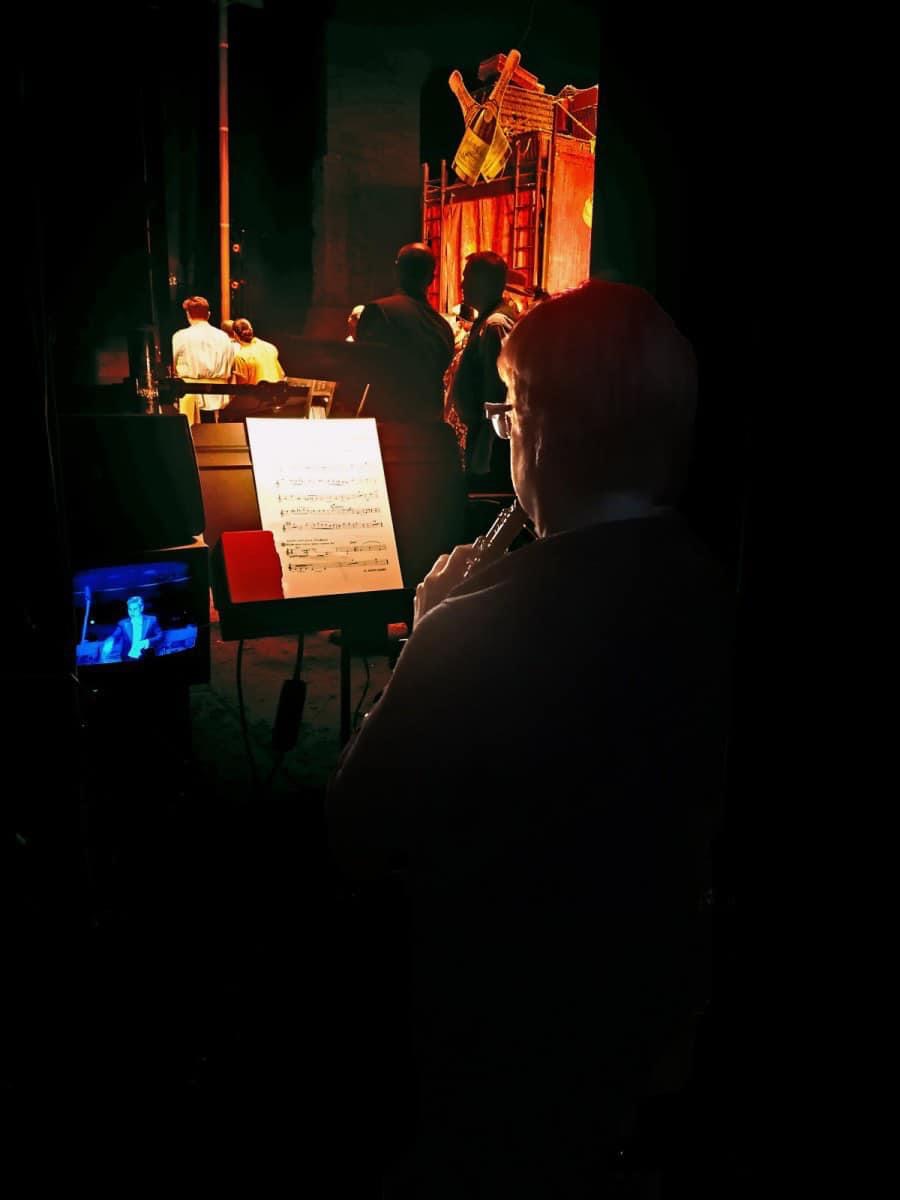

Similarly, there’s no question that solo artists are the ones that most often produce the high C’s, the inimitable concluding pianissimo high note that tapers to nothing, the character representation that is so authentic that one forgets that this is theater. Those of us working in the house every day and every night do not begrudge the resulting plaudits, the cheers at the end of arias, nor the curtain calls at the end. They are justly deserved and, many times, many of us in the pit and in the wings are also openly cheering and applauding along with the audience.

However, calling any of these solo artists “MET Stars” seems somewhat misleading and disingenuous to me.

“… how is any solo artist a ‘MET Star’ any more than he or she is a ‘Covent Garden star,’ a ‘Wiener Staatsoper Star,’ a Bayerische Staatsoper star,’ or a ‘La Scala star?’”

For one thing, the MET cannot make sole claim to these artists nor how they are received; these artists experience the same merited accolades everywhere they perform. By design, their profession dictates that they travel to and sing in MANY opera houses and halls. And, incidentally, solo artists negotiate and sign their own individual contracts with each venue, i.e., they are not employees of any one opera house but are classified and paid as independent contractors.

Considering that, how is any solo artist a “MET Star” any more than he or she is a “Covent Garden star,” a “Wiener Staatsoper Star,” a Bayerische Staatsoper star,” or a “La Scala star?”

Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Opera’s full-time employees are there day after day, night after night, and season after season, performing our OWN feats of technical and aesthetic brilliance.

Many of us, myself included, were here well before some of these artists made their MET debuts. And many of us will be here long after they retire. Some of us played and worked at the OLD MET (which closed its doors fifty-five years ago!)

So, secondly, doesn’t that make full-time tenured employees stars in our own right?

Stars come and go. Meanwhile, the rest of us have been busy playing, singing, dancing, rehearsing, accompanying, coaching, prompting, pounding nails, moving sets, wiring, powering, lighting, storing and handing out essential props, calling personnel to the stage for the smooth execution of the opera without unnecessary traffic jams in the wings or missing characters or props, sending people onstage at JUST the right moment, perfectly timed to the music and action—and delaying such when occasionally needed for various reasons, arranging and moving chairs and stands and delicate equipment like harps, pianos, and percussion equipment, securing sheet music for every opera, making sure all cuts or changes are made for EVERY person—solo artists, chorus members, orchestra personnel, conductors, and retrieving parts to make additional changes when they inevitably happen prior to and during the rehearsal period for any number of reasons—a conductor wants to make or open a cut, a singer requests that an aria be transposed, stage action necessitates more or less music, etc. We are also taking measurements, cutting fabric, sewing costumes, repairing existing costumes, touching up scenery, making wigs, putting makeup on cast members, fitting cast members into costumes, laundering costumes, ironing costumes, meeting with directors about their ideas for sets and costumes, loading sets on trucks to be taken to storage units in New Jersey…whew! I’m out of breath!

“…we are a well-oiled machine that has been decades in the making.”

If this all sounds complicated, trust me: it IS. If it sounds like there are a lot of different groups of folks charged with a lot of responsibility, there ARE. But because every one of these employees is the crème de la crème in their respective fields, most of the time, the effort involved in any one performance is hidden from view. It’s “all in a day’s work” for us: our art or craft has been refined and honed through years and years of doing what we do and passing along the best of those traditions to those who come in to the MET family either directly from school or from other theaters.

In short, we are a well-oiled machine that has been decades in the making.

To paraphrase the great conductor Arturo Toscanini, perhaps the only true stars are in heaven.

So, then. Are WE the MET Stars?

To paraphrase the great conductor Arturo Toscanini, perhaps the only true stars are in heaven.

Leave a reply to Susan Laney Spector Cancel reply